Seeing the wood amongst the trees

- Dylan Parry

- Jan 7, 2020

- 2 min read

Updated: Dec 23, 2020

If communication is all about informing or persuading another person, then a critical element in the dynamic is surely that other person. A human being.

But we know that humans are often beguiling, frequently irrational and always unique. It's hard to predict with any certainty exactly how one will respond to…well, pretty much anything.

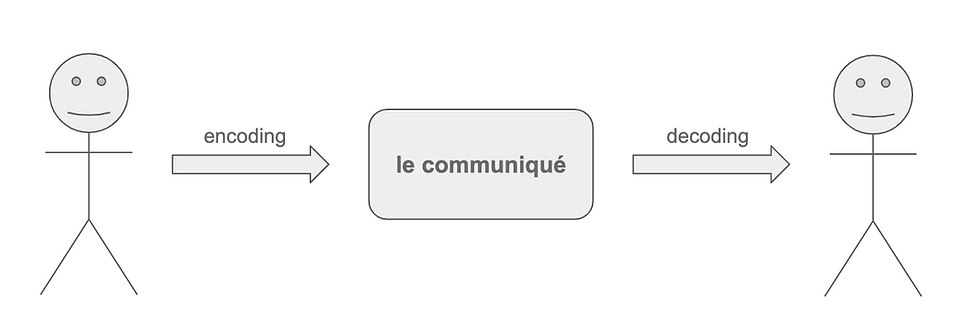

In most communication, there are three key elements in play:

Communicator (a person, or group of them)

Message (inc. the medium)

Receiver (a person)

Our job as communications professionals is to shape that bit in the middle (the message). But here I want to talk about that last piece in the chain – the receiver.

About 360 million people speak English as their first language. But they don't all speak it in the same way. We know that Americans, for instance, don't speak quite the same English as us Brits. No siree, Bob! Likewise the lexicon in my native West Country can be gurt lush, in ways that would raise an eyebrow anywhere east of Didcot power station.

But I don’t want to state the bleedin’ obvious: that language varies along the lines of region, age, interest group and all manner of other things. I want to go a little bit further and recognise that we each have our own uniquely personal relationship with language. We have our own biases – the result of our experiences, values etc – that shape the way we speak: the words we favour, those we don’t, how we order them, how direct we are, how casual we are. That’s why ’tone of voice’ is a thing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, those personal biases that determine how we shape communication also affect how we receive communication. That's why one person's warm arm-around-the-shoulder is another’s cloying encroachment. And why one person’s smart double-entendre is another's ‘WTF' exasperation. (Acronyms and jargon are a case in point, actually.)

So if we want to move people, we shouldn’t imagine our audience as a huge amorphous aggregate, before proceeding to hurl the least disagreeable message we can think of at the middle of the blob. Why? Because in hoping to vaguely connect with everyone, we risk missing them all.

We should instead take time to picture the individuals on the other end of the line. The human beings who will – if we’re lucky – process our words (and graphics, audio, images...) by themselves, in their own personal way.

Of course, if we’re talking about mass communications, we can’t tailor the message to everyone. (Though I'm told robo-copywriters are making great strides.)

But by picturing the individuals down the line, we avoid many of the inaccurate assumptions we tend to make when thinking of ‘people’ en masse. In turn we give ourselves a chance of constructing a message that feels more direct, more personal, and harder to ignore.

Comments